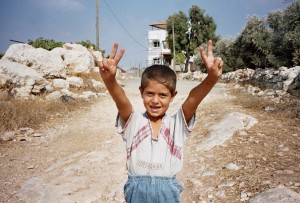

We had been waiting for the Israeli soldiers to come and open the gate in the “separation fence” for two hours here in Jayyous, allowing the farmers to get to their fields. The sun was already high, children were already late for school, and the day was getting shorter for harvesting. Olives, as precious as gold in this community, were overripe and starting to dry up on the trees. And we continued to wait.

We had been waiting for the Israeli soldiers to come and open the gate in the “separation fence” for two hours here in Jayyous, allowing the farmers to get to their fields. The sun was already high, children were already late for school, and the day was getting shorter for harvesting. Olives, as precious as gold in this community, were overripe and starting to dry up on the trees. And we continued to wait.

As the hours passed by, Mustafa looked at me and my mobile phone and demanded: “Why don”t you call soldiers?” “I can”t!” I shot back. But he didn”t believe me. He didn”t realize that I was as helpless as he was. After all, as far as he was concerned, foreigners are supposed to fix everything that needs fixing. We accept the lot with pride, and feel badly when we cannot fix it. We don”t know how to share powerlessness. Hence, a search for it has become my spiritual journey in this little corner of the Holy Land.

For far too long, we have designated ourselves as “fixer-uppers.” When we face a situation with no possibility of fixing, we get frustrated and sometimes take inappropriate actions. Meanwhile, some people have the capacity to live with helplessness and share it with others, often accompanied by soothing tears.

Recently soldiers stopped all those who were younger than 35 and did not allow them to go to work in the fields for reasons of “security.” Women bunched together and cried as another day”s harvest was lost, while men resorted to destructive behaviour such as vandalizing the fence. Louise, a journalist from Denmark, joined the women who were prevented from going to the fields and cried with them. Hearing this, a British volunteer from an international solidarity organization said: “That must have been the most healing thing that happened to those women–sharing tears. I wish I could do that.”

The trouble is that even though we have come to Palestine and Israel to accompany and journey with our brothers and sisters on their rocky road to peace, we still hold advantages. These advantages prevent us from fully sharing in the lives of our brothers and sisters. We have foreign passports, for example, which allow us to go where Palestinians or Israelis often have difficulty entering. It often takes hours for Palestinians to go through checkpoints, if they are allowed through at all. Israeli peace activists are prohibited from entering areas that are supposedly under the total control of the Palestinian Authority. However, we can go through checkpoints in three seconds by flashing our passports. Maren, a medical student and Ecumenical Accompanier from Denmark, thought that her presence helped an ambulance go through a checkpoint in a shorter time than usual recently. But her Palestinian colleague said to her: “I wanted you to see what a checkpoint really is like for us.”

All of us carry mobile telephones, which we are required to keep on at all times, ostensibly for our safety. Recently the soldiers were once again late in arriving so I telephoned HaMoked to find out the reason for the delay. HaMoked is an Israeli human rights organization, which is called the “Organization for the Defence of Individuals” in English. It maintains up-to-date information about the conditions at checkpoints and gates and helps Palestinians who are having difficulty getting through. It often intervenes by contacting the authorities. The representative at HaMoked said: “I will call you back as soon as I find out what the problem is.” A second later a jeep pulled up, and the gate was opened, a complete coincidence. A man on a donkey saw all this and flashed the thumbs up sign as though to say: “Thanks, you did it again.” “No, I didn”t. It was just a coincidence!” I thought. But as far as he was concerned, a foreigner did his magic bit again.

People often ask: “Do people in the village accept your presence?” Of course most do but sometimes I wonder. There are a few older men and women who don”t seem to care if I am there or not. I see this old man who always comes to the gate with a donkey cart, wearing a traditional kaffiyeh. He always wears an old worn-out dress jacket underneath the kaffiyeh. He usually sits on a stone near the gate, looking at the ground while patiently waiting for the opening. He never says anything to anyone. I try to sit next to him to somehow engage him. He always ignores me and keeps looking down at the ground between his shoes. I can feel his embarrassment over the whole humiliating situation. Why does he have to depend on foreign occupying troops to open the gate so he can get to his field? Worse still: why does he have to endure the presence of foreigners to solve his problem for him? I saw the same proud but humiliated eyes in the soup kitchen in Montreal. While others seemed defeated and servile, some looked disdainful. I see others who are like him, often older men and women. Some may think I am reading too much into his stoicism but I don”t think I am. Why? Because I know the humiliation of being on the receiving end of charity.

I was desperately hungry once and Americans gave us food. They saved us from death by starvation. This was in Japan after its surrender in World War II in 1945. Was I grateful? I have to say I was; after all I am still alive today. I should have been, if I wasn”t. But what I remember more vividly was a feeling of humiliation rather than gratitude. Receiving charity is humiliating. Having to depend on other people always is. We feel strongly that we should be independent and self-sufficient. That self-confidence makes us proud creatures who believe that God made us in his own image as beings only slightly below Him. This is the source of our dignity. It makes sense, therefore, that Jesus said: “It is better to give than to receive.” We have to realize, however, that we may not always be privileged to give.

When I went to Africa, I was called a “missionary.” The term was everywhere around me. I went to the Missionary Orientation Conference in London, Ontario and to L”Ecole Missionaire in Paris. It was assumed that I knew something “they” didn”t, and had something to give which “they” hadn”t. I am glad that those days of Western conceit are over. This is why I like the notion of accompaniment very much. I like it especially because of the situation people are facing in Palestine and Israel. We in the West bear a lot of responsibility for creating the problem here. The Western Christian world persecuted the Jewish people for millennia. We barely acknowledged the suffering of Palestinians for nearly half a century. Yes, we have helped cause many of the problems here but let us not compound our mistakes by behaving as though we know so much and can do so much to fix things here. The only thing left for us to do is to share in the humility and powerlessness of people.

Tad, Ecumenical Accompanier

Jayyous